Breathing Architecture

We all do it – every day, every second of every day, in and out, like clockwork. It’s one of the few things that unites us all across the globe, regardless of race, gender, age and ability. Most of the time we do it without even thinking about it – other times it can be harder. Sometimes we lose it, sometimes we hold it, sometimes we run out of it – but usually we catch it again, fall back into the old rhythm, and forget we’re even doing it.

I’m talking, of course, about breathing.

Perhaps it seems obvious to point out that humans breathe: but the last two years have thrown our universal right to breathe into question. The Covid-19 crisis, pollution, the climate emergency, and Black Lives Matter have all forced us to think about breathing – and to notice the times when respiration can be difficult or even dangerous.

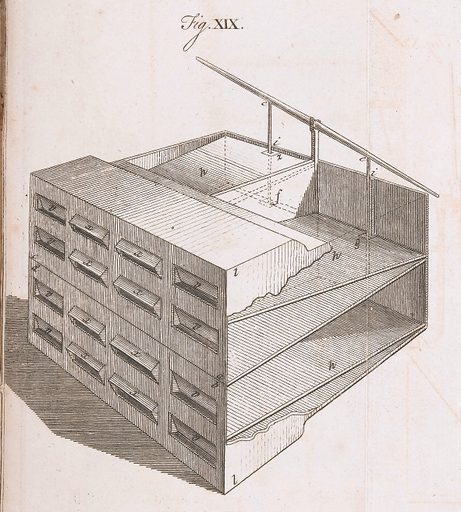

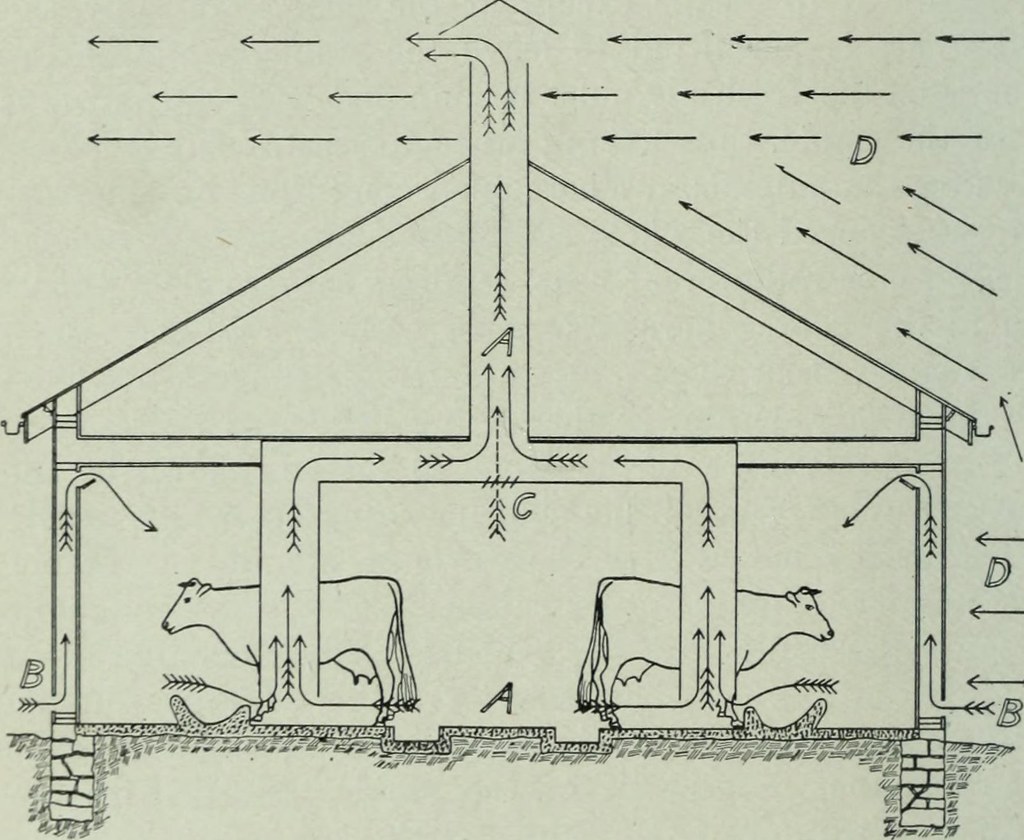

Architects have always had to think about breathing. Even the very earliest inhabitable buildings incorporated rudimentary systems of natural ventilation, through open fires and gaps in the structure. Windows, for example, aren’t only there to let in light or reveal a picturesque view – they’re also necessary for letting fresh air into a space, which is vital for the health of a building, as well as its inhabitants. Without a regulated flow of fresh air, buildings can become damp, mould can begin to grow, and viruses can be more easily transmitted amongst people and pets.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, architects have thought increasingly about how to design spaces with viruses in mind. During the pandemic, the availability of fresh air, not to mention having adequate interior space to socially distance, became a major concern. The virus reminded us that, although breathing keeps us alive, it can also be dangerous, and the buildings we inhabit have to take account of this.

Polluted air – another instance when breathing can be dangerous – has also been a pressing concern for architects. How can we design buildings that safeguard against – or even help to detoxify – unhealthy air? The prevalence of green walls and roofs in recent years has had the double effect of raising oxygen levels in both indoor and outdoor environments, as well as keeping the air cool in warmer months through a process known as “evapotranspiration.”

Recently, designers have even been using algae to purify the air in indoor spaces. In AirBubble, a children's play pavilion designed by EcoLogicStudio, algae is used in solar-powered bioreactors to remove carbon dioxide and pollutants from the air – so that children can play safely inside.

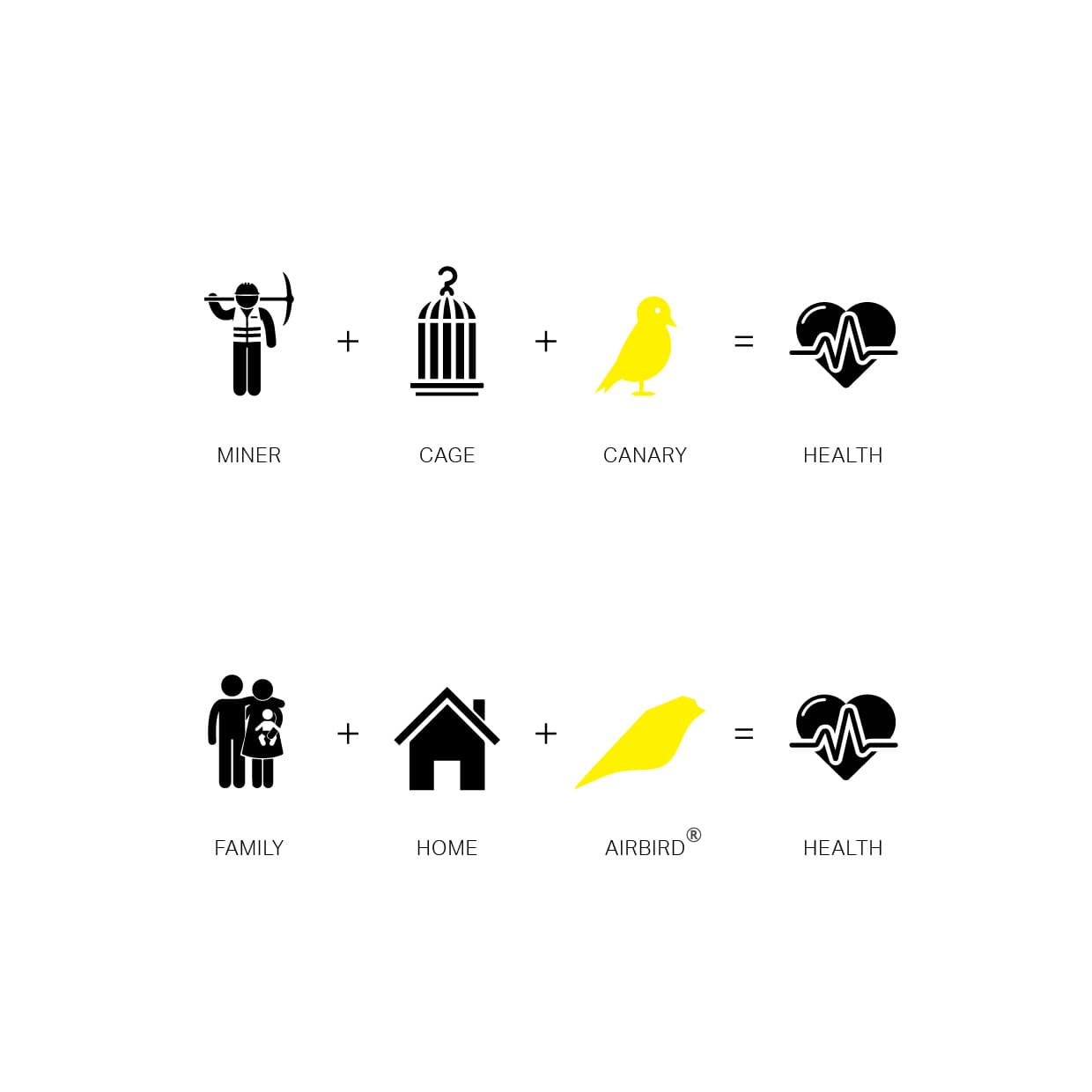

Elsewhere, GXN, the innovation wing of Danish architecture studio 3XN, has designed AirBird®, which chirps when it senses that the air quality is unhealthy in the home or the office. Inspired by canaries used years ago in coal mines to alert miners of toxic gas leaks, AirBird® measures CO2, temperature and humidity every few minutes and uses this real-time data to prompt action to improve air quality – and thereby the health and well-being of people in indoor environments.

But not all threats to breathing come in the form of toxins and viruses – sometimes, humans threaten each other’s breathing through violence, or through the simple fact of forgetting how to breath together. In April 2021, in response to both the Coronavirus pandemic the Black Lives Matter movement, artist Ekene Ijeoma constructed a temporary installation in Brooklyn called Breathing Pavilion. Comprised of a ring of inflatable illuminated pillars, Breathing Pavilion invited people to come together and breathe with the rhythm of its pulsing orange lights and gently humming fans.

Ijeoma, Breathing Pavilion. Photo credit: Kris Graves. Courtesy of Studio Ijeoma.

Ijeoma, Breathing Pavilion, Photo credit: Jesse Winter. Courtesy of Studio Ijeoma.

These designs might be new, but they only serve to remind us that architecture has always been about breathing: whether that has to do with maintaining clean, fresh air, or bringing people together to breathe collectively, architecture and design shape the ways that our living, breathing bodies move through and inhabit the world around us.

Words by Mae Losasso