Cornelia Parker Annual Art Lecture

This second annual RIBA x Grimshaw foundation featured Cornelia Parker. The following explores some of the ideas she raised in her lecture.

From the beginning of her career, Cornelia Parker’s work has spoken to the transient nature of buildings, the built environment and the climate. For her lecture, Parker provided an insight into her creative process, speaking on explosions, clichés, identities, things falling apart at the seams and being put back together again.

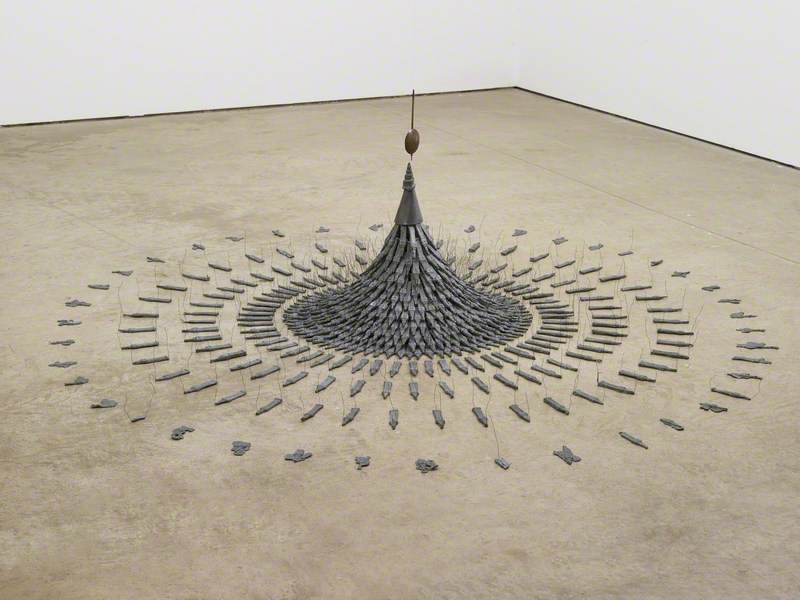

For 10 years at the start of her career, Parker lived in Leytonstone, until her house was ‘knocked down to build a link road for the M11’. And it was around this time that Parker began playing with the forms of iconic structures. Parker cast a souvenir of Big Ben in lead hundreds of times – until what remained no longer resembled the famous clock tower. Arranging and suspending the casts in a splattered out circular form, almost as if it was disintegrating, Parker created a ‘crude abstraction’ of the structure – a Fleeting Monument (1985) that plays with the cliché of something that was supposed to stand forever, falling apart.

Similarly challenging the importance of a structure by eroding its environment is Subconscious of a Monument. With this piece, what appears to be lumps of ordinary dirt are suspended on wire, consuming the room it is displayed within. However, the work is actually made from earth that Parker salvaged from beneath the Leaning Tower of Pisa. In suspending the lumps of clay from the ceiling, almost like they have returned to their molecular form, Parker unearths the importance of the clay ‘laying underneath this famous monument for 1000 years now. It's seen the light of day, and it is kind of happy about it’. Parker describes this work as an ‘exploded view’ – calling attention to the individual fragments of the very thing that kept the lopsided structure somewhat upright, but also highlighting the fact that even monumental foundations can be discarded.

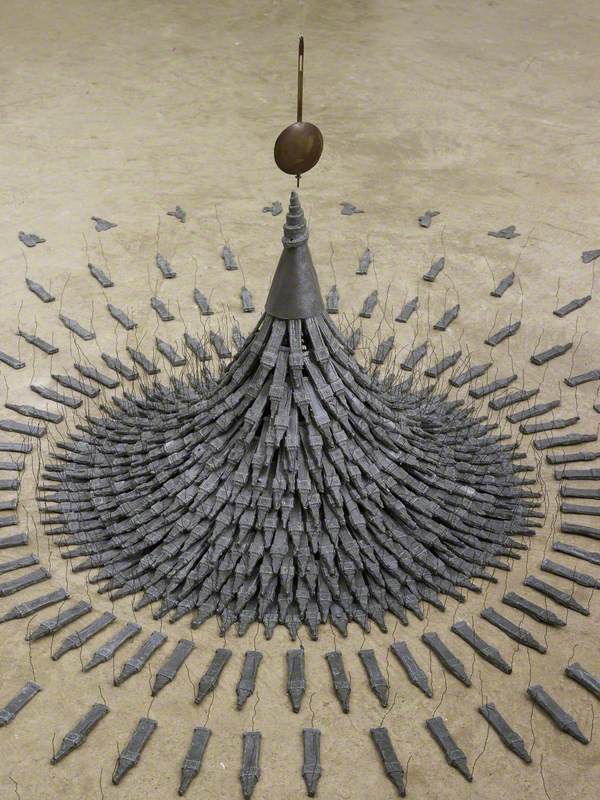

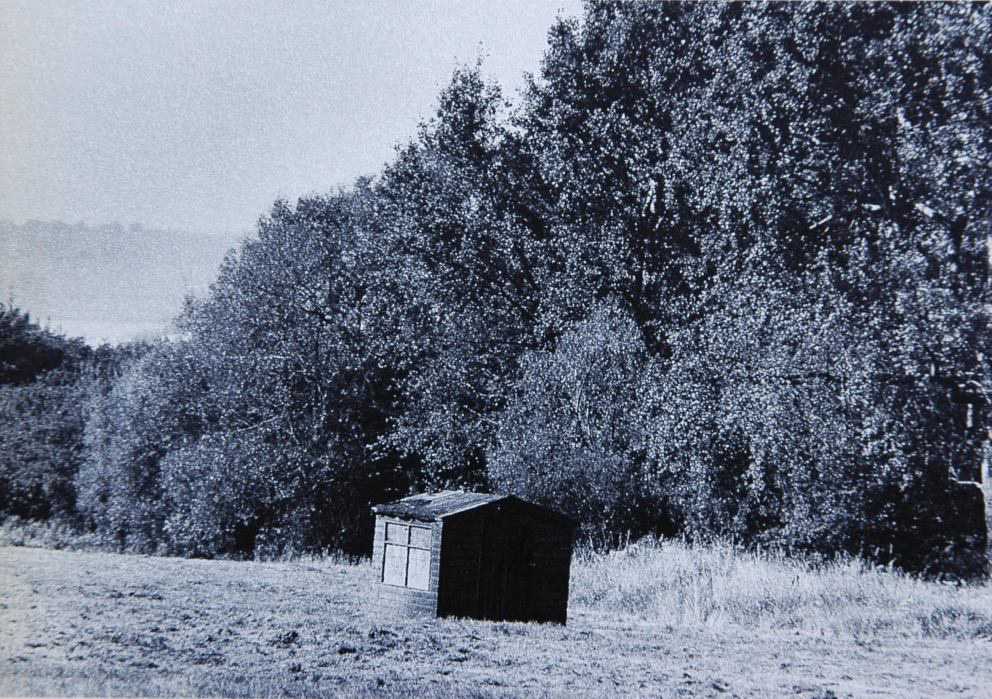

With her work Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), Parker reconceptualises the notion of an exploded view, taking it to its most literal sense by exploding a garden shed – the black hole of the garden, where things disappear never to be found again – with the help of the British Army. Parker explains that ‘Cold Dark Matter is a scientific term to describe matter in the universe we know exists, but we can't measure it. It's unfathomable. And then an exploded view is the opposite. So, this work is trying to do an exploded view of an explosion. We see explosions all the time on the news, the war, terrorism attacks, demolition, and it somehow seems like an archetypal image.’

Charred wooden fragments of the shed and the remnants of the objects inside are given a second life, suspended in the air, ghost-like, as if frozen at the epicentre of the explosion.

A lightbulb hangs at the centre of the piece – throwing shadows around the space, reanimating the fragments, and holding them all together.

In 1997, the idea of the destruction of structures took Cornelia to Texas, a place with an unpredictable climate, so she knew ‘could possibly find something that would be struck by lightning,’ as she explained at the recent lecture. After just a few days in the state, Parker was informed by the fire brigade that a church had been struck by lightning. ‘Wow, that's amazing – It’s supposed to be an act of God to have a lightning strike.’, she quipped.

As Parker collected the charcoal pieces from the charred church, she noticed that after just two days, the church was being rebuilt – a common trade in that area. ‘Why do they keep getting struck by lightning?’ Parker asked. The response: ‘They get arsoned. And it is mainly black congregation churches that get arsoned’. Thus, of that natural destruction came Mass (Cold Dark Matter), a piece that suspends the charred fragments of the church structure in a concise cube formation, giving a sense of order to the chaos. And a few years later, following the burning of a black congregation’s church by a group of Hell’s Angels, came the ‘diptych’ Anti Mass. Together, the works act as an eerie commentary on the natural and the hateful acts of destruction that we find in society.

With her most recent film The Future: Sixes and Sevens (2023), Parker trains her lens on impending chaos and crises. The film (which was shown at the Hayward Galleries exhibition Dear Earth), sees Parker hand the mic over to young six- and seven-year-olds, asking them questions about their future in the face of the climate emergency. The responses of the children vary with one child wanting to be ‘a mathematician. . . because I could work on quantum gravity and I get a Nobel Prize’, and another wanting to be tall enough to reach the top shelf of the fridge. With this work, like many of her others, Parker allows space for comedy, but crucially doesn’t let the audience forget that this is ultimately a crisis that we have the power to change.

Whether recording the colourful machinations of children, inflicting cartoon deaths upon innocent objects, or transforming the way iconic symbols or artworks are viewed by the public, there is a clear sense of humour that runs throughout Parker’s artistic conceits. In turn, Parker tackles political institutions, social constructs, or climate emergencies, in a way that holds a mirror to the sometimes comedic, sometimes terrifying chaos that exists in the world that is slowly coming apart at the seams.

Hopefully, as Parker has proved time and again, sometimes the most destructive events can prove the most constructive.

By Elise Nwokedi