Mixing Metaphors: Buildings and their Doppelgängers

Last night I stepped up to the plate and bit the bullet – but it all went pear shaped. I came home and hit the sack, and I’ve been feeling under the weather ever since. I should have known it was a wild goose chase, that I would get caught red-handed, and now I’m having kittens over it.

We’re probably all familiar with the rhetorical trick of metaphor, in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it isn’t literally applicable. Of course, I didn’t really ‘step up to a plate’, or ‘bite a bullet’; I’m not literally ‘under the weather’ or ‘chasing wild geese’ – or ‘having kittens’, for that matter. Nevertheless, we all know what these phrases mean – and we accept them in spite of their obvious nonsense. Why? Because metaphors give colour to descriptions. They help us to picture one thing, by relating it vibrantly – and often playfully – to something else.

We usually associate metaphors with language and literature – whether we encounter them in idioms – like in the examples above – or in plays, poetry and fiction: “All the world’s a stage,” wrote William Shakespeare, “and all the men and women merely players.” We know that the world isn’t literally a stage, but we enjoy the image – and it helps us to think about our relationship to the world anew. Metaphors often have this effect, injecting new life into things that have become familiar or old hat (there’s another for you).

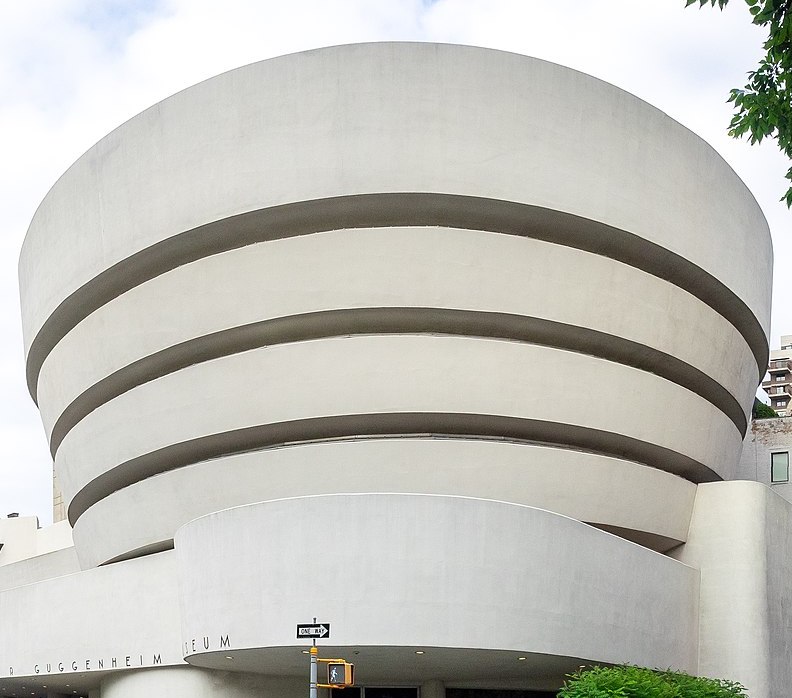

The architect Charles Jencks believed that architecture was a certain sort of language, and that it could be broken down into all the same components: words, phrases, syntax, semantics – and, of course, metaphor. “People invariably see one building in terms of another,” Jencks wrote, “or in terms of a similar object: in short as a metaphor. The more unfamiliar a modern building is, the more they will compare it metaphorically to what they already know.” You’ve probably done something similar yourself – look at that building! It looks just like a giant spinning top! And Jencks is right – the less like a conventional building it looks, the more it seems to resemble something else.

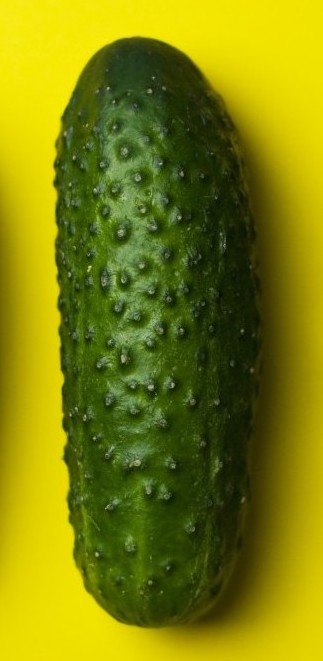

Lots of buildings end up assuming the names of their associated metaphors. Take, for example, 30 St Mary Axe – better known as the Gherkin for its curved and elongated shape; or 122 Leadenhall Street, aka the Cheesegrater; or The Fenchurch Building, better known as The Walkie-Talkie. You only need to take one look at these buildings to see why the metaphor stuck.

Or take St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, with it’s tiered white steeple – remind you of anything? That’s right, the traditional white wedding cake – though in this case, the story is a little more complex. Rumour has it, that in the 18th century an apprentice baker fell in love with his boss's daughter. To impress her he wanted to make a showstopper of a cake. Gazing across the London skyline, St Bride’s caught his eye – and voilà, the tiered wedding cake was born!

Relating oddly shaped buildings to more commonplace objects helps to anchor us – we can make sense out of the unfamiliar by attaching it to something we know well. But it works the other way around too – choose an everyday, household object and think about what a building might look like that was modelled on it.

It’s time to get (back) to the drawing board – and start building castles in the air!

Words by Mae Losasso