Minsuk Cho's Archipelagic Void

The architect speaks to Grimshaw Foundation about his design for the Serpentine Pavilion 2024.

Like a shooting star jutting into the centre of the Serpentine South lawn, Minsuk Cho’s Archipelagic Void takes its place as the 23rd Serpentine Pavilion.

Built largely from timber, the structure is arranged across five unique ‘islands’:

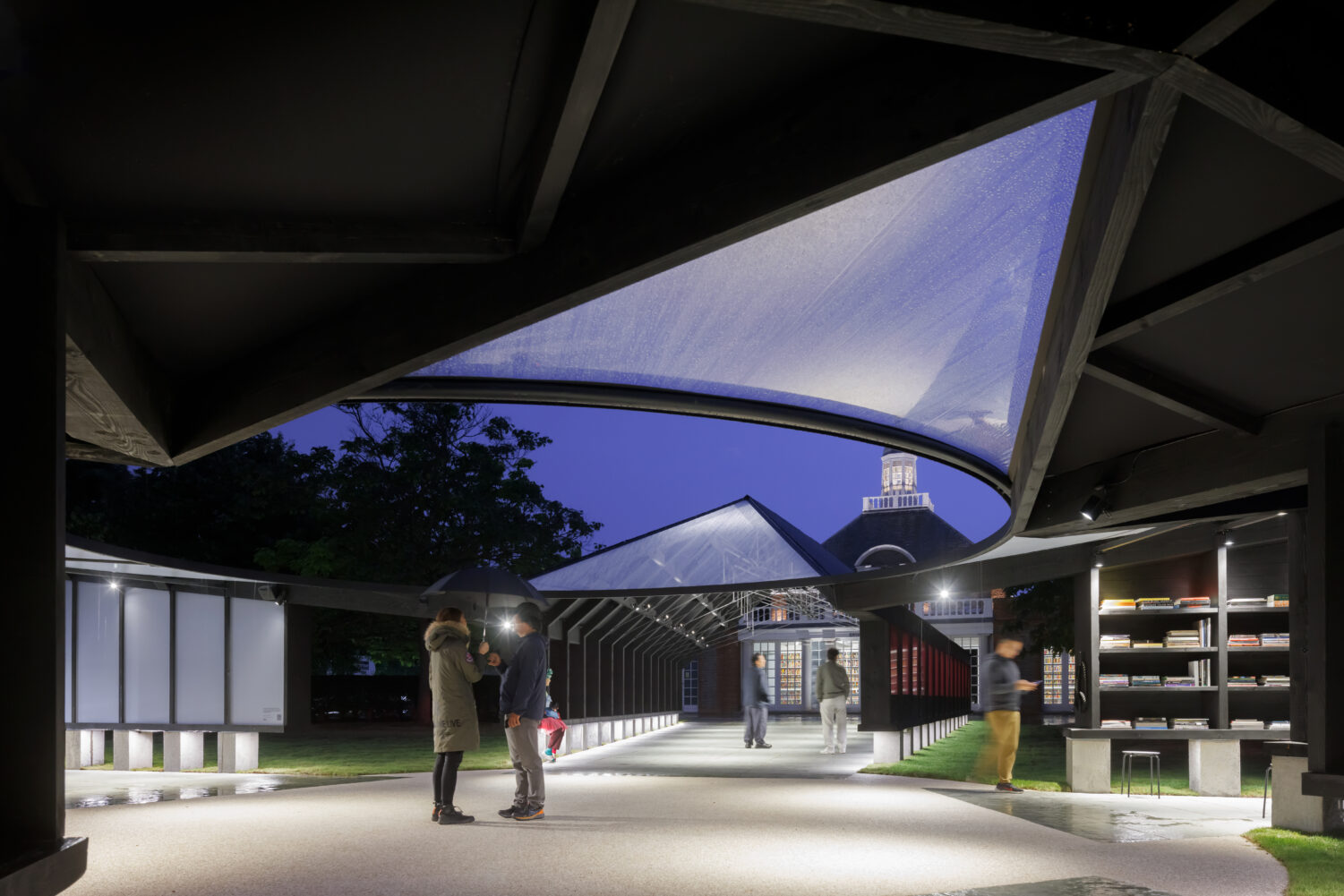

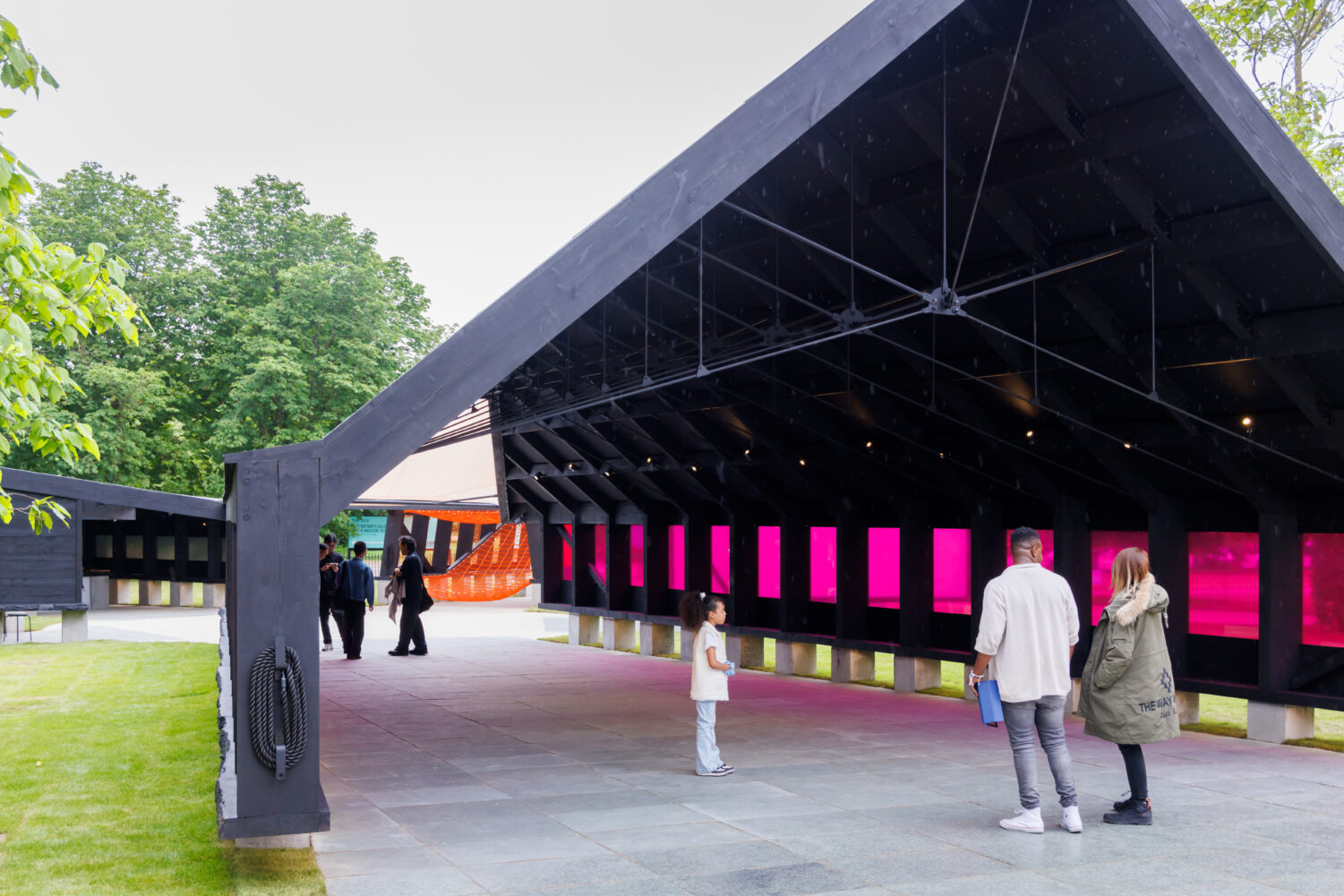

The Gallery, which features a sound installation by musician and composer Jang Young-Gyu titled The Willow is <버들은> and Moonlight <월정명> ; The Auditorium, which is lined with benches and a pink tinted screen; the interactive Play Tower, which boldly reaches up towards the sky, with its orange netting inviting visitors to climb and play; the Tea House, that hosts a small café; and The Library of Unread Books by artist Heman Chong and archivist Renée Staal, that features donated unread books. All these elements surround a central circular ‘void’, taking inspiration from the layout of traditional Korean houses that feature a ‘madang’, an open courtyard located at the centre.

We asked Minsuk Cho about his striking Pavilion, his use of materials, the idea of light and space and the importance of creativity. Read his responses below:

Could you talk about the title ‘Archipelagic Void’ and the idea of creating five ‘islands’, that serve as distinct spaces as opposed to one singular structure?

In our initial research of past Serpentine Pavilions, we found that circular and rectangular geometries were the most prevalent, with about two-thirds displaying a distinct geometric form while the rest were free-form. Our approach diverged from this norm by first creating a void. By leaving the centre empty, we shifted away from the traditional central architectural focus, not to be antagonistic, but rather allowing for new narratives and possibilities to emerge at the periphery.

Responding to the unique conditions presented by the Serpentine South gallery and surrounding landscape, we defined the void through the five 'islands.’ Each segment of the Pavilion is unique in its shape and form, yet together they define the eight-meter diameter circular void at the centre. Each island contributes one-fifth of this eight-meter diameter circle, creating a space that balances between openness and enclosure. Assembled, the parts become a montage of five distinct covered spaces and five open spaces of surrounding park in between. This makes the Pavilion site-specific to the Serpentine South lawn, but also allows it to perform similarly on any other site.

The Pavilion is, at the same time, site-less. After its five-month stay at the Serpentine, these five structures can potentially be moved to an unknown location and reassembled in 120 different possible compositions to adjust to a unique topography and surroundings. We were quite excited about this idea, which was driven by the specific condition of the Serpentine South lawn but offers a vast range of options. In a way, it’s a discovery and an invention simultaneously. Even within this complexity, the Pavilion encourages individuals to freely approach, enter, and exit the pavilion, without a prescribed path, thus promoting a sense of freedom and community.

How did you choose your materials? The black timber, for instance, and the vibrant orange netting in the ‘Play Tower’. Was the way they relate or contrast to the surroundings an important consideration?

Designing this year’s Pavilion was an opportunity for my practice to diverge from the in situ concrete construction we frequently use in Korea. Historically, Korean architecture is mostly, if not all, timber structures on stone platforms. The importance of sustainability, the way we source materials, the construction processes, while simultaneously complying with the building codes of the Royal Parks, it was many factors that guided us towards a timber structure.

Although we have used timber in our practice, it has mostly been engineered wood, such as glue-lam, as was the case for some of the past Serpentine Pavilions. This was the first time we used natural timber, specifically Douglas fir sourced from Surrey, only 30 km away from London. It was very exciting for us.

The Pavilion's colour scheme was designed to create a complementary contrast to the lush green of the surrounding park. We explored different atmospheric qualities by using pink tints to contrast and complement the green grass. The black-tinted polycarbonate of the Tea House, almost like sunglasses, provided added protection for the cafe staff and created a calm, blurry, Richter-esque painting effect. The polycarbonate and PVC membranes are 100% recyclable.

Experiencing the completed Pavilion, I noticed that the structural rhythm creates a playful movement of colour and light as you move through and experience the various, unprescribed sequences the structure and its interstitial spaces offer.

From above, the pavilion looks like a shooting star, yet from the inside the darkness of the wood provides a striking contrast between light at shade, especially with the central void. Can you talk a bit about the significance of light in the pavilion?

The notion of light in the Pavilion is part of the multi-sensory quality of architecture, which I enjoy. It runs parallel to the tactile nature of this year’s Pavilion. The materials choices and how they are composed have cultural references but also add to the relationship formed between our bodies and architecture.

Contrast is quite important for us as we suggest five covered spaces to provide shade and protection from the strong summer sun and rain. At the same time, the spaces created between these ‘islands’ and the open areas have a strong contrast. This resembles the environment formed by a cluster of small, one-storey structures around a void. In the traditional Korean residential typology, the void, called a madang, is interesting because it is almost forbidden to plant anything in it. Instead, it is filled with the brightest possible earth soil so that it reflects light back into the shaded deep spaces of the timber structure under a pitched roof. This creates horizontal views through the space, from the outside in, from the front to the back, and the back madang, etc., resulting in an array of sequences of shade and light.

I could not have predicted or simulated the dynamic play between the natural elements, and this built environment. There is an openness and framed views of both the interior and exterior when necessary. Each ‘island’ has a different way of connecting to the outside, or back in, and uses various light filtering mechanisms, whether it’s the structural composition itself, or through the spectrum of colours and transparencies that the windows and roof membranes offer, that create quite a pleasant interplay with the natural light.

A question we ask artists, architects, and the students the Foundation works with in our workshops - What does creativity mean to you?

Creativity involves being curious and engaging with the unknown, seeking to connect various elements, whether tangible or intangible. In architecture, this means exploring space and time, nature and man-made structures. There are countless ways to make connections if you possess a keen curiosity and a desire to discover unknown possibilities and new ways to connect the offerings of the world.

Minsuk Cho’s Archipelagic Void will be at the Serpentine South lawn until the 27th October 2024.