The Royal Academy's Entangled Pasts

Entangled Pasts: Art, Colonialism and Change is at the Royal Academy, London, until 28 April

The story of Entangled Pasts begins at a table.

Before even entering the exhibition spaces nestled within the Royal Academy of Arts, you are struck by the powerful sight of Tavares Strachan’s triumphant sculpture The First Supper (Galaxy Black), 2023. Made from bronze, a galaxy black patina and gold leaf, the sculpture features thirteen larger than life historically significant black figures, gathered around a table adorned with food from across Africa and its diasporas. For Strachan, the work is a “sharing of histories, science, geography, sculpture, archaeologies, materiality, and psychologies”. It exists in “a time and a place before now” and, in reimagining Leonardo’s ‘The Last Supper’, draws attention to the rich lives and stories of the figures gathered around the table. The piece talks about mankind’s “evolutionary origins in Africa”, yet in doing so, it also highlights “the struggle for progress”. Placed in the centre of the RA’s courtyard, it is the perfect piece to introduce viewers to the exhibition.

Looming behind and above Strachan’s courtyard table, is a statue of Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the RA. It’s his figure that you walk past before entering through the main doors of the building. And it’s his words that introduce you to the entangled nature of this exhibition. When the Royal academy was founded in 1768, Reynolds deemed the institution to be an ‘ornament’ to Britain’s Empire.

At the time of making this statement Britain’s Empire spread across parts of Africa, Europe North and Central America, and India. The establishment of lucrative trading merchants and the Transatlantic Slave Trade meant that Britain was a prosperous and deadly Imperial Power. For the RA to be an ‘ornament’ of such a colonial force speaks to the state of the Nation, and the state of the Arts at the time. Bringing together over 100 artworks from across the RA's 250-year history, Entangled Pasts explores the role of art in ‘shaping narratives of empire, colonialism, enslavement, resistance, abolition and indenture’.

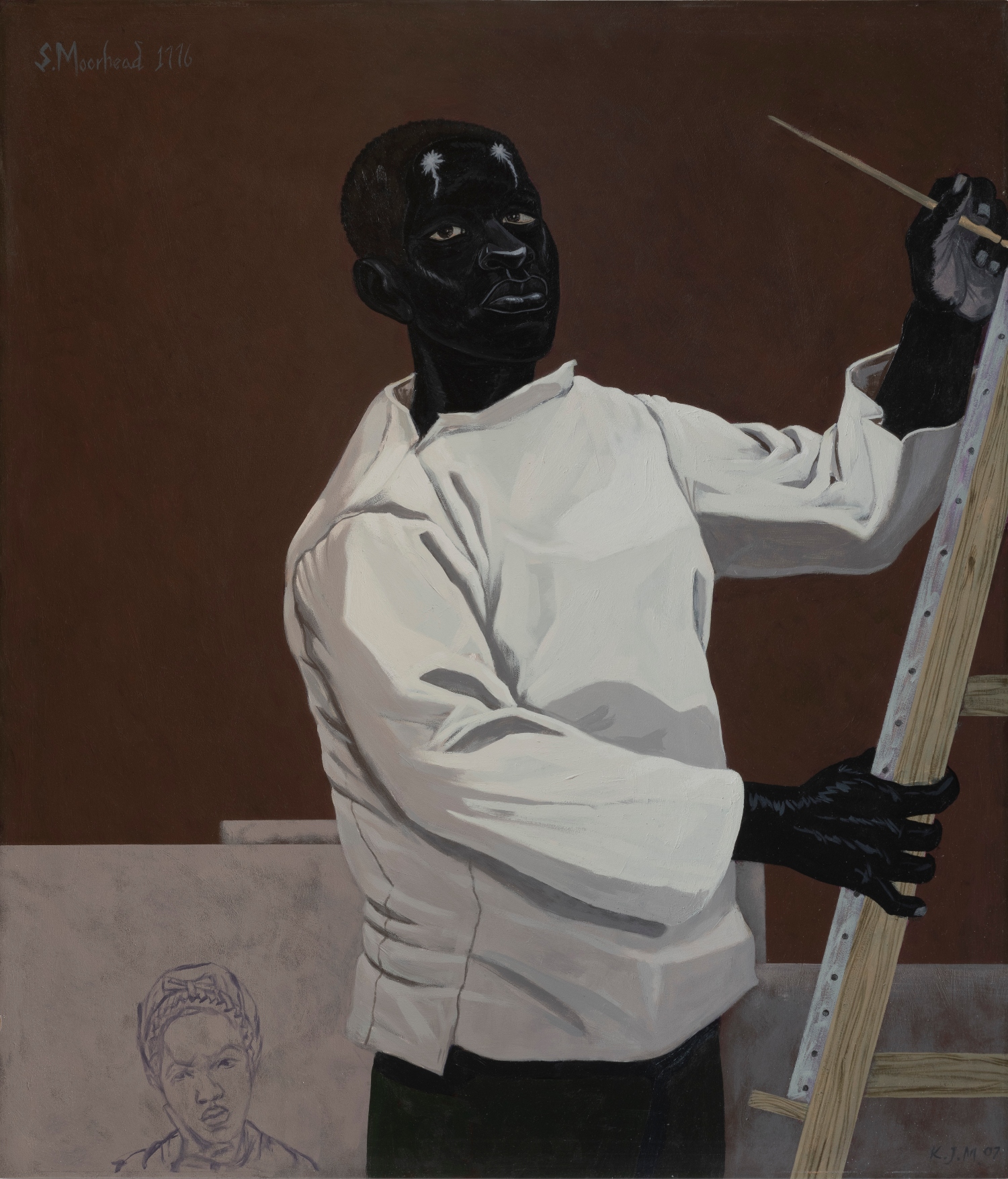

Like Strachan’s Courtyard sculpture, the first room of the exhibition has a similarly striking impact. Designed by JA Architects, the octagonal room recentres the black figure, placing Bust of a Man (1758) by Francis Harwood, carved from black stone, on an octagonal plinth at the centre of the room. The sculpture is surrounded by portraits of black sitters, some of whom are unknown, who would have been living in Georgian Britain, ranging from Ignatius Sancho (by Thomas Gainsborough) to Kerry James Marshall’s ‘self’ portrait of Scorpio Moorhead, an enslaved artist working in 18th Century Boston who unfortunately has no surviving works.

Yet embedded into the upper levels of the same walls of the neoclassical galleries are busts of prominent, and Eurocentric renaissance artists and architects, (Michelangelo, Christopher Wren) alongside Royal Academy artists (Reynolds, Flaxman), suggesting an artistic lineage and shared reverence. The team from JA Architects, uncomfortable with the hierarchy that the placement of these figures suggested – looking down on the black figures – obscured four of the busts with mirrors. These mirrors amplify and reflect the central bust in the room, further recentring the black figure, but they also place the bust alongside those that remain uncovered, allowing a dialogue between the figures and their histories. It also allows a dialogue to emerge with the viewer, as they also see themselves reflected in the exhibition, and in turn the history of the RA.

This sense of reflection and entanglement continues throughout the exhibition, with Hew Locke’s Armada (2017-19), suspended in the adjoining room surrounded by historical depictions of maritime exploits empire and race, such as John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark (1778). Constructed from found objects or from scratch, some of Locke’s fleet of boats are modelled on historical vessels such as HMT Empire Windrush (1948), the Mayflower (1620) and those of the East India Company. Yet the ever-pertinent theme of migration is echoed throughout the installation, with each boat heavily customised with tokens, coins, bags, or the possessions of an entire family. As Locke said himself, the work depicts ‘the ghosts of the past floating alongside the realities of the present’.

Works by historical and contemporary Royal Academicians are placed alongside each other throughout the exhibition. Lubaina Himid’s 2004 multifigure installation Naming the Money spreads across two rooms in an ‘ode to human resilience, community, and creativity in the face of extreme cruelty and adversity'.

Yinka Shonibare has two works on display. Women Moving Up (2023) is an ‘optimistic’ and ‘aspirational’ work that highlights the ‘desire for emancipation’. Justice For All (2019) is a reimagining of F.W Pomeroy’s Lady Justice (1905-06) that sits on the dome of the Old Bailey, featuring the figure with a globed head, adorned in African textiles. Shonibare often uses because of the material’s global nature (they are Indonesian inspired fabrics, produced by the Dutch and then sold to the African Market).

Sonia Boyce’s four panels Layback, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great (1986) subvert the Victoria adage ‘lie back and think of England’ and depict Britain’s major Empirical territories (Cape Colony, India, and Australia), with a final panel featuring Boyce’s self-portrait gazing at the viewer, willing them to confront Britain’s colonial exploits.

This exhibition does not turn away from the traumatic ‘entangled’ pasts and colonial histories enmeshed within the foundation of the RA but confronts them head on in a sprawling display that took me two visits to work through. The exhibition arose after the 2020 murder of George Floyd and following Black Lives Matter protests, that lead many in Britain to reconcile with the nation’s colonial histories and injustices as seen with the toppling of the Colston statue in Bristol. Yet I couldn’t help but think about what happens once the exhibition leaves the RA? While the final room asks, ‘Where to From Here’, I felt as though there was no real answer to that question. Should there not be a permanent space for contemporary figures to be displayed at the RA, amongst the Turner's and the Gainsborough’s.

Exhibitions come – they are appreciated – then they go. More often, monuments and statues are permanent. They endure to such an extent that they become enmeshed, entangled even, with the communities they reside in. They become beacons – but should they not also be reflections?

By Elise Nwokedi