Quiet Power

Veronica Ryan wins the Turner Prize 2022

POWER! POWER! POWER!

VISIBILITY! VISIBILITY!

WE ARE VISIBLE PEOPLE!

These are the words that visual artist Veronica Ryan OBE triumphantly proclaimed as she stood on stage at Tate Liverpool on Wednesday 7 December to receive the 2022 Turner Prize. In winning this award as a 66-year-old, Montserrat-born woman, Ryan becomes the oldest person and the second Black woman ever to receive the prize.

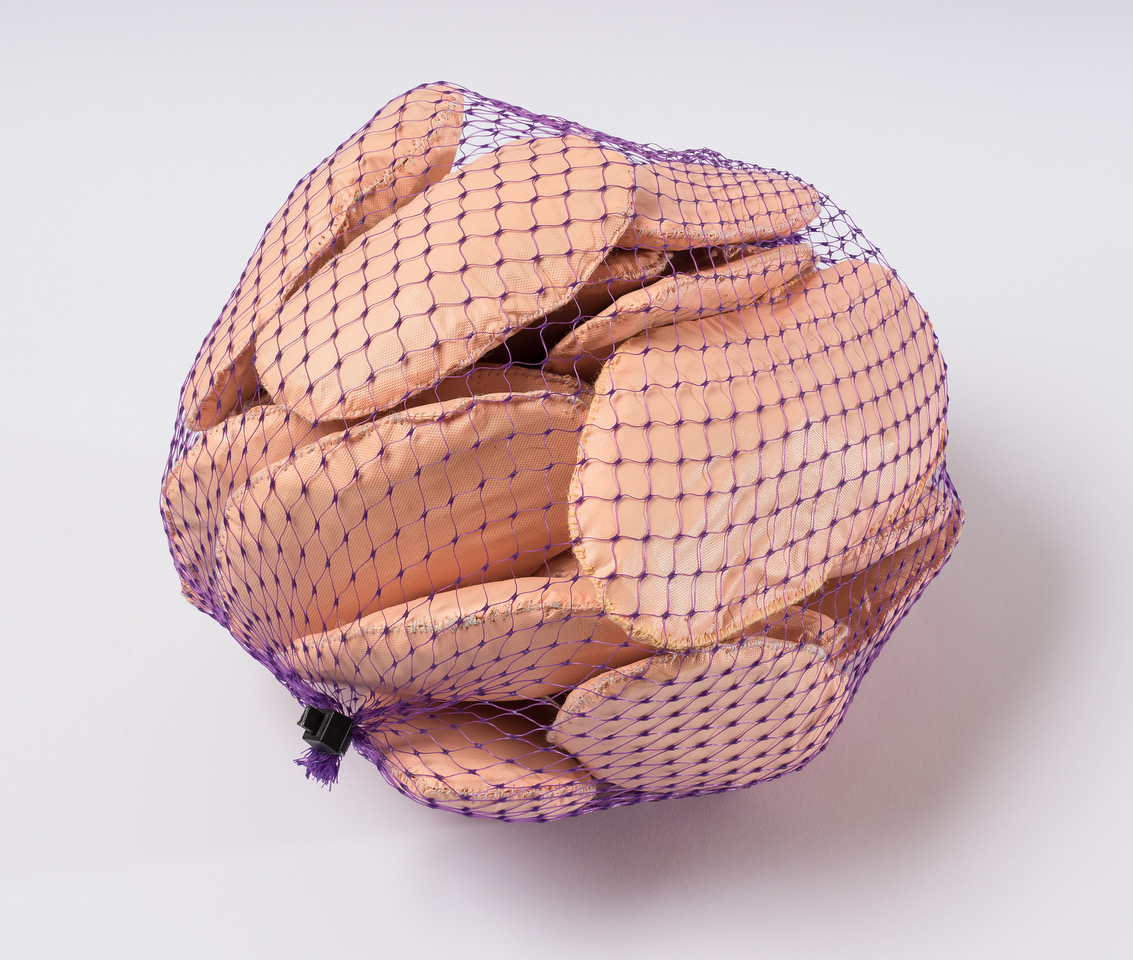

Ryan was nominated for her solo exhibition Along a Spectrum at Spike Island, Bristol and for her Hackney Windrush Art Commission in London that featured three fruits, Custard Apple (Annonaceae), Breadfruit (Moraceae) and Soursop (Annonaceae). Both installations are rooted in Ryan’s upbringing as a member of the Windrush generation, Ryan moving from the Caribbean to London with her family when she was a child. We see the influence of this community not only in the objects Ryan sculpts, but in the materials used to make them such as the bright neon fishing line pouches that evoke those found in the bustling market stalls on Ridley Road.

Yet one word continuously crops up in relation to critical responses to Ryan’s work: Quiet.

Speaking on Ryan’s win, Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson said that Ryan’s work is potentially the “the quietest and slowest burn” of any recent Turner winner. Jonathan Jones hails Ryan as a “sensational choice as Turner Prize winner”, calling her a “quietly great artist”.

Perhaps it is the fact that Ryan works with sewing and embroidery, fruit and vegetables, fabric and pillows that invite this idea of quietness and softness. The handmade nature of her artwork and the familiarity we have with her materials creates this sense of safety. Yet while Ryan’s objects may appear soft and inviting, they can be hard and sturdy to the touch. Soft pillows cannot be rested upon as they are stacked high towards the ceiling and held together with large needles. Ripe fruit cannot be bitten into as it has been cast in bronze or marble.

'Dem Mash You Up Man' embroiders unsprouted custard apple and soursop seeds into a large fabric tapestry to symbolise the importance of environment in a seed's germination

Equally, some of her works might be pebble-sized, but they have a global resonance. In particular, the Along a Spectrum exhibition reflects on the emotional and socio-political implications of the current global climate. Using a mix of natural materials such as seeds, fruit stones and hand sewn items, Ryan looks at the impacts of environmental change, displacement, and isolation in the face of the pandemic.

We see this in pieces like “Dem Mash You Up Man”, which embroiders unsprouted custard apple and soursop seeds into a large fabric tapestry to symbolise the importance of environment in a seed's germination. The title comes from a Caribbean colloquialism, but Ryan states that “is really talking about a kind of behaviour which is to do with anxiety and dysfunction”. Though unassuming to the eye, the power behind this message is profound.

Quiet does not mean unheard. Quietness does not minimise the power and weight that Veronica Ryan’s artwork carries. For art to strike us and move us deeply, it does not have to overwhelm our senses in a bright array of LED strobes. It can do what Ryan’s work does so impactfully: remind us of home comforts, and unsettle our foundations, not letting us forget the impacts of being uprooted and resettled. And what is more quietly visible than a permanent public art installation?

Quiet does not mean unheard

Sitting in the heart of Hackney, next to its oldest building, St. Augustine Tower are Ryan’s three precious fruits, cast in bronze and marble. Their quiet yet permanent visibility within the community means the history of Windrush is intrinsically woven into the history of the area and so can never be forgotten. Wine is spilled on them by people party in the nearby pub. They are sat upon by people taking a moment’s pause to eat their lunch. Just as life is full of moments both loud and peaceful, so works of art can affect us in unexpected, subtle ways.

By Elise Nwokedi